|

By: Mary Young

Oahu Island News

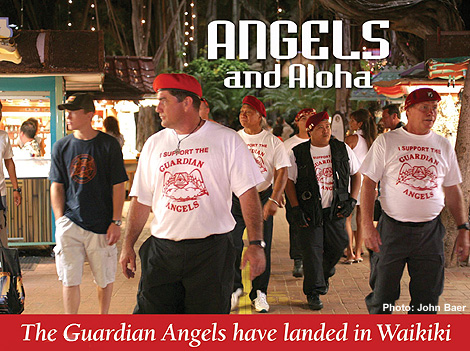

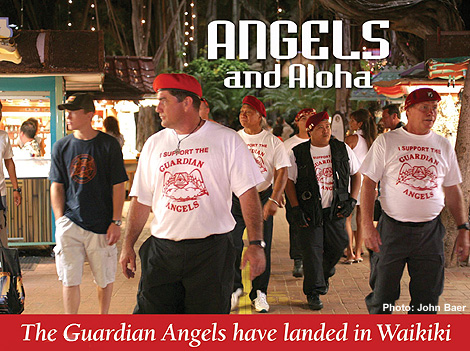

Twenty-five

years ago in the Bronx, a cadre of young volunteers known as Guardian

Angels began patrolling New York’s subways and streets. Working in pairs

and wearing the red berets that became the group’s signature, their

courage and high visibility helped to bolster public confidence and deter

crime. The Guardian Angels’ founder was a 25-year-old fast food

restaurant manager named Curtis Sliwa.

In May 2004, the Guardian Angels of Japan Inc. and the Guardian

Angels Western U.S. Regional office announced plans to open a Hawaii

chapter. The leader, Ricardo Garcia, 39, is an Ewa Beach resident and

certified Guardian Angel. He patrolled with the Guardian Angels as a

teen-ager growing up on Chicago’s south side. Garcia says he resolved to

be an angel after seeing the 1981 movie “Fighting Back,” based on

Sliwa’s story.

Sliwa founded the Guardian Angels during an era of widespread crime in New

York City. Most notorious was the harassment and terror on the subways. At

the same time, the city was taking budget cuts and law enforcement

officers were being laid off. The timing was right for the Guardian

Angels: Sliwa was charismatic and a good promoter, his multi-racial squad

was photogenic and the Guardian Angels’ rise coincided with other

successful anti-crime initiatives in the city. They won the support of

former New York mayors Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg and other

civic boosters. For the most part, they were successful in fending off

accusations of vigilantism and overzealous behavior in their ranks.

The Guardian Angels’ nonviolent methods were so successful that chapters

have been established in over 30 cities worldwide. In addition to safety

patrols, Guardian Angels teach self-defense, provide disaster assistance

and partner with other community organizations. In 1995, the Angels

established an on-line safety education and cyber-neighborhood watch

called “CyberAngels.”

The Hawaiian Guardian Angels face different challenges than those Sliwa

encountered in the 1980s. Criminals have become more sophisticated, the

islands’ drug problems persist and budget cuts at all levels of

government are making volunteer efforts more essential than ever.

Patrolling the streets will not be enough.

“The patrols are the most famous part of the program,” said Sebastian

Metz, director of the Guardian Angels’ Western U.S. region, “But the

Guardian Angels program is primarily a program of taking young people and

giving them an opportunity to be heroes in their community.” For

example, he said, Angels might train others in crime prevention techniques

or volunteer for clean-up projects. “Until they can start actually doing

good to help other people, the concept of helping out is only that: a

concept,” he said.

Metz, speaking by phone from his home in Denver, said the success of the

local program will depend on how well it resonates with the young

recruits.

“Really, we want a program that’s drawn from [places like] Farrington

High School,” said Metz. “Because that’s where we can help out the

island in two ways: Not only do we have some reassuring presence on the

streets, we’re also taking young kids that might otherwise be drawn into

[drug] use or some other bad choice and taking them away from that

choice.”

In the meantime, Garcia’s recruits – mostly in their 30s and 40s –

are training after hours in donated space at Kokua Mau Work Center in

Pearl City. Six recruits expect to graduate in September. They are

learning martial arts, first aid, CPR and state laws regarding harassment,

trespassing, and the justifiable use of physical force. They also learn

how to make a citizen’s arrest, a seldom-exercised right that is

available to every citizen.

In June, Garcia and recruit Raymond Manuel attended the Guardian

Angels’ annual convention in New York. “On our first night we had to

make a citizen’s arrest,” said Garcia. He and Manuel were walking

through the lobby of their Bronx hotel when they saw someone hit a fellow

Angel in the face for no reason. “We had to arrest the guy for

assault,” said Garcia, who detained the perpetrator until the police

arrived.

One night a week, the local trainees patrol with Garcia in Waikiki.

“We’re here to be the eyes of the police and to help the police in

whatever they need us,” said Garcia. “The police cannot be everywhere.

And it takes two minutes to rob somebody. In an hour, you can rob probably

about 40 people.”

Deputy Chief Paul Putzulu of the Honolulu Police Department acknowledged

that Garcia has contacted HPD, but no meeting had been scheduled as of

press time. “Basically, if

they’re going to be out there just having a presence and they’re

calling us so we can respond, that’s fine,” said Putzulu.

“We understand the police have a lot on their plate,” said Metz.

“For us, we just want an opportunity to prove ourselves … I think

they’ll find that we are a good asset, and they can use us in a number

of different ways if they so choose.”

Garcia said they will eventually patrol other neighborhoods, but Waikiki

has been good for training and for public relations. The red berets get

some double-takes, but Garcia says the feedback on the street has been

positive.

Margaret and Tom Fawcett, visiting from the United Kingdom, were strolling

down Kalakaua Avenue on a recent weeknight. The couple said they were glad

to see Guardian Angels. “It’s quite reassuring, actually,” said

Margaret. “I’ve seen tourists getting their bags pinched.”

Sharon White from Philadelphia, having an ice cream cone at the

International Marketplace, said, “I think the more eyes the better out

there.”

Garcia has already spoken to some Oahu neighborhood watch groups about

crime prevention. The Hawaiian Guardian Angels are joining the American

Red Cross disaster response team. Future plans call for offering

assistance to groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Drivers and to local

schools through the Junior Guardian Angels. Geared for children between 7

and 11, the early-prevention program teaches values and instills a sense

of purpose that youngsters may not receive at home. “They do the same

training but they don’t patrol,” said Garcia. “Instead, they do

something like a beach cleaning day. The kids wear red berets, pick up,

clean up, make sure the area is beautiful, maybe next time they have a

party.”

Garcia works for the Transportation Security Administration. The former

Marine and Gulf War veteran was stationed at Camp Smith from 1985-1991 and

at Marine Corps Base Hawaii-Kaneohe Bay from 1998 until he left the

service in 2001.

He wears his long hair in a neat ponytail and speaks with polite reserve,

using “ma’am” and “sir.” He displays the Marine Corps eagle,

globe and anchor emblem on his beret.

Making the decision to start a Hawaii chapter was difficult, he said.

“Once I got out of the military, I waited one whole year to make sure

that everything was correct and I was ready to take the challenge,” he

said. “I had the opportunity to do police work in the Marine Corps and I

did a great job, thank God. But I wanted to make sure that I still had it.

Because if I didn’t, I wasn’t going to do it.”

Most of the trainees contacted Garcia after seeing news reports of the new

Hawaii chapter. “I must have had about 30 to 40 people call me the same

day, and my phone didn’t stop,” Garcia said. “When they find out

that we don’t carry weapons – that’s the biggest question, do you

carry weapons – well, we do not carry weapons. We believe that if you

carry a weapon, you’re giving the aggressor the opportunity for him to

feel threatened and pull out a weapon. That’s not our objective.”

“I want my children, and the elderly and other children, to be able to

walk the streets at night, daytime, in the middle of the day, in the

middle of the afternoon, without being worried,” said Garcia.

Bobby Murray, a Wahiawa resident, said he joined the Guardian Angels

because of high crime near his home. “I drive through it every day on

the way home from work,” said Murray, “And I‘ve always wanted to do

something about it but never had the means. Now I have the means.”

.

The

Hawaii chapter of the Guardian Angles

can be reached by calling:

808-689-8854

or online

www.guardianangels.org or

Hawaii@guardianangles.org

|