|

By:

John Goody Foot

by foot, Bill Adams and Louis Otto climbed their way up the east wall of

Haiku Valley, leaving the rope in place after each assault. At the end of

21 days of steady work, long since invisible through the clouds to those

below, they achieved the summit. Clinging

to the northernmost spur of the hogback, they looked around. They could

not see more than 20 feet through the dripping mist; it was cold, windy

and scary. Sitting, exhausted, on the wet ground, Adams swung one leg over

the far side and straddled the mountain. The fog broke a little. “God

Almighty!” he grunted. “Look, Louis.” The

drop on the east side was almost perpendicular, all the way down 1,800

feet to the next valley beyond. They were perched on the razor’s edge of

the summit ridge. Then,

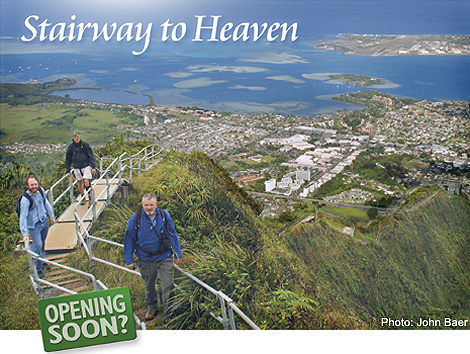

for a moment, the clouds blew off and the enormous panorama of the whole

region lay below them. There, to windward, the shallow curve of Kaneohe

Bay glimmered pale emerald in the sunlight, bordered by vivid turquoise of

the shoals. The naval air base at Mokapu seemed a cluster of white dots

around the base of Ulupau. “Pretty,

by God!” said Bill fervently. The

first two pioneers reached the summit ridge of Puu Keaheakahoe in 1942 –

and so began the construction of Haiku Stairs. Today,

the trail these men pioneered up the face of Puu Keaheakahoe is closed,

but according to Honolulu Managing Director Ben Lee, there is “great

promise” for reopening the stairs. If all goes as expected, the

“Stairway to Heaven” should open for hikers to experience the

windswept cliffs and beautiful views of windward and leeward Oahu within

the coming year. Opposition

to reopening the Haiku Stairs has been voiced by some residents of the

bordering neighborhood. The root cause of complaints, often heard at

meetings, is that people cut through their neighborhood, take up street

parking spaces, make noise, cause dogs to bark and generally disrupt the

neighborhood. In response to these issues, the Kaneohe Neighborhood Board

has formed a task force to investigate residents’ claims before the

stairs are reopened to the public. The

Haiku Stairs were originally constructed so antennas – the working end

of a top-secret naval radio station that would communicate across the

Pacific – could be stretched across Haiku Valley. At first, the stairs

were just a line of ropes hanging from metal pickets. Shortly there after,

the ropes were replaced by wooden ladders and then by wooden steps. Over

time, the wooden steps were replaced by the present-day metal ladders,

which closely resemble a series of ship’s ladders connected end-to-end.

Although the stairs have endured for more than 60 years, the remains of

several sections of the original wooden ladders are still visible, strewn

across the cliff sides where they were discarded. When

the metal stairway was completed in 1953, it was able to provide

continuing access for maintenance to the antennas and communications

control link that is perched near the summit of Puu Keaheakahoe. Today,

these unique and historical structures along with the Haiku Stairs are

historic properties eligible for protection under the National Historic

Preservation Act. They

are in need of such protection. In

1972, the radio station in Haiku Valley was transferred from the Navy to

the Coast Guard to operate as an Omega navigation station. During that

time a small and discreet group of local hikers came to use the Haiku

Stairs to gain access to the ridge of the Koolau Pali. This use of the

Haiku Stairs was not an issue until the climb was publicized in a Honolulu

daily newspaper. Then, the secret was out. By

the mid 1980s, the Coast Guard registered up to 20,000 people a year to

climb the Haiku Stairs. These hikers would enter the valley through the

gate (which is now locked) in Haiku Village and park at the transmitter

site or along the loop road. This situation continued until the stairs

were vandalized in 1987. Three stair sections, at the steepest portions of

the climb, were torn out and thrown down the mountain. After that

incident, the stairs were closed to hikers. Shortly thereafter, the

obsolete Omega station was closed and the Coast Guard left the valley. The

stairs once again gained a relative measure of peace, as only those hikers

who knew the trails, and were willing to scramble across gaps of nearly

vertical rock with only the aid of frayed, old, fixed ropes, could ascend

the trail. It remained that way until the Coast Guard, approaching a land

transfer to local government, threatened to tear out Haiku Stairs. A

public outcry ensued to save the stairs. That protest, bolstered by the

fact that the stairs are a historic structure and that the environmental

impact caused by their removal would be substantial, persuaded the Coast

Guard to relinquish the Omega station, with the stairs intact, to its

highest-priority claimant, the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands. The

valley was of no direct use to DHHL as its terrain is too steep and rugged

for cost-effective development. But it was a good bargaining chip for more

useful land, and the city and county of Honolulu eyed the Haiku Valley as

a mountain park. Due to the expectation of a land exchange with DHHL, the

City of Honolulu appropriated and spent over $800,000 to repair the

stairs. The newly improved stairs were expected to become one of the focal

points of a nature and cultural preserve in valley. The repair to the

stairs proceeded on schedule – not so did the negotiations for a land

exchange, or for temporary access to the stairs through the Hope Chapel. Once

repairs were completed, hikers, by word of mouth and news articles,

returned. Lacking a designated parking area or trail access, they began

routing through neighborhoods and climbing fences erected to keep them out

– thus, the seeds of yet another community dispute were sewn. While

some of the neighbors seemed to take it in stride, a small group of

residents in the Hokulele subdivision were angered that hikers used the

neighborhood as a trailhead. A few even began calling for complete removal

of stairs and extended their objections to the creation of a park in the

valley. Trespassing hikers, it seems, have created a sentiment among some

to fight anything that would bring other people into the neighborhood.

Although security guards now keep the majority of trespassing hikers out,

that sentiment unfortunately lingers among a few neighborhood residents. Where

do we go from here? Twenty

years ago, before the Hoku-lele subdivision was constructed, access to

Haiku Stairs was through the Coast Guard Station in Haiku Valley. In

that period and since, when many

trespassing hikers have made the climb, no serious injuries have

been re-ported. This is a far better safety record than many of our beach

parks and other mountain trails. The Haiku Stairs

are a jewel in the crown of Oahu’s No

one disputes that residents have a right to peace and quiet in their

community. Fortunately, there is a way to accomplish this by restoring

appropriate public access to the Haiku Stairs. Residents

do not have the right to close public access to mountain lands and trails

because they do not want other citizens to travel through their community

on public roads. Throughout Oahu, access to mountains and beaches is

gained through neighboring communities. We go to the beach in Kohala,

Lanikai, and Kailua by parking in neighborhoods and walking paths between

houses. Nearly every mountain park in the Koolau Mountains is reached

through a neighborhood, from Aiea Heights to Mauna Lua Valley and Kuliouou.

Haiku Valley is no different; in Hawaii, mountain lands are not the

private preserve of those privileged to live at their edges. The

number of people who can use the Haiku Stairs is limited by the physical

size of the stairs themselves. Under proper management, 100 people a day

would be a reasonable number of hikers to ascend the stairs, although past

records indicate the number of actually hikers would be substantially

less. Having too many hikers on the trail would not only be impractical,

it would adversely affect the climbing experience and potentially damage

the stairs and the surrounding environment. This small number of hikers

(spread over an entire day), along with adequate parking and management in

place, would not create a problem passing through the neighborhood. It

certainly did not in the past. We

need to work together as a community to provide safe, legal access

to Haiku Stairs. To accomplish this, we also need to work with

renewed energy on the land exchange for Haiku Valley that would enable a

cultural and natural preserve there, and to provide managed access for

Haiku Stairs. As

of press time, the Kaneohe Neighborhood Board’s Task Force proposal is

to use a parking area at the Windward Community College, and access the

stairs by following a fenced pathway bordering the state hospital to the

H-3 service road, which leads to the bottom of the Haiku Stairs. This

initiative, which does not address access into Haiku Valley, answers many

issues raised by residents. Likewise, consideration should be given to use

of Haiku Road for access into Haiku Valley via the Omega Station gate, as

was done in the past. This suggestion avoids using roads inside Haiku

Village, and Haiku Road could be gated at the bottom to control access.

Measures such as these, combined with effective control and management of

the stairs, continued discouragement of trespassing and public education,

will work. The alternative – to close Haiku Stairs and the Haiku Valley – is simply short sighted and anger-driven. Rather than solving the trespassing problem, it will only prolong it and provoke a destructive fight within the community. It will also leave open the possible for future economic uses of the Haiku Valley that are potentially far worse for the community than a passive natural preserve and park. The

solution to all of this is there to be had, we must work together as a

community now, John Goody is the president of the

Friends of Haiku Stairs and a long-time windward resident. He is a retired

U.S. Marine, and retired Vice President of the consulting firm of Belt

Collins. Formerly a resident of Haiku Village, he and his family have been

climbing Haiku Stairs since 1977. |