|

|

|

|

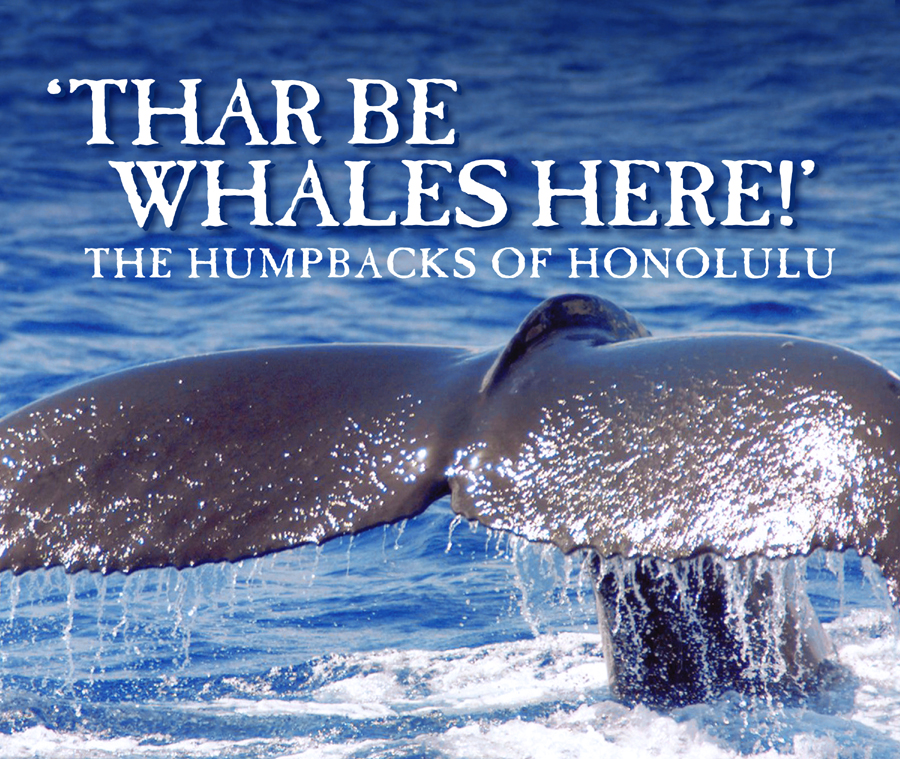

PHOTO: ATLANTIS ADVENTURES

By W. KNOX RICHARDSON

“For the first time in our now ten weeks’ passage from the Hawaiian

Islands… we heard, day before yesterday, that life-kindling sound to a weary

whaleman,‘Thar she blows!’ The usual questions and orders from the deck

quickly followed.

“‘Where away?’

‘Two points on the weather bow!’

‘How far off?’

‘A mile and a half!’

‘Keep your eye on her!’

‘Sing out when we head right!’ ”

Thar she blows!

That is a excerpt from “The Whale and His Captors,” the 1853 recollections

of a Boston missionary, the Rev. Henry T. Cheever, who three years earlier

sailed the Pacific Ocean as a passenger aboard the whaling ship, “Commodore

Preble.”

Though seemingly archaic, “Thar she blows” is still heard everyday on the

waters off Oahu, but not from whalers — from visitors and kama‘aina alike as

they take to the azure seas in search of whales.

The wooden-hulled, three-masted whaling ships of the 19th century have long been

replaced by modern watercraft ranging from 140-passenger, multi-decked dinner

cruisers with weather-proof viewing to inflatable, outboard Zodiac boats that

virtually guarantee getting splashed.

Harpoons have been traded for digital cameras. Just spotting a whale and

capturing its photographic image is presently a suitable trophy for a day’s

outing. But there is more to the story than that.

Whales were important to a post-Cook Oahu beginning first in the early 1800s as

the island’s second source of export income following sandalwood. Until the

discovery of petroleum-based oil in the late 1850s, whale blubber (reduced to

oil by boiling it) had been the young United States’ primary source of lamp

oil. Hawaii-based whalers supplied most of the blubber.

With the age of exploration coming to an end, many a young man dreamed of

joining up with a whaling company and sailing to the mystical South Seas. In the

1840s, one such young sailor — a 21-year-old New Englander named Herman

Melville — signed on with the whaler Acushnet

but later jumped ship while in port in the Marquesas Islands.

Several months afterward, Melville arrived in Honolulu and spent nearly a year

on Oahu and Maui observing the whale trade. Subsequently, he gave the world the

classic allegorical morality tale of good and evil, “Moby Dick.”

In “Moby Dick,” Ahab is the

paradoxical captain of the whaling ship, Pequod.

Having previously lost a leg to the Great White Whale, Ahab is all consumed with

hate and revenge.

Today, Cale Wofford is the captain of the excursion vessel Navitek berthed at Pier Six in Honolulu Harbor. He isn’t vengeful,

but he still has the singular mission of tracking down and finding whales —

not to harm them, but to greet them with a ship full of admiration and aloha.

Five days a week, he maneuvers the sleek, high-tech craft out to sea where just

a mile or so off shore he patiently tracks down the elusive humpback whale using

only his knowledge and experience. Cale, like Melville’s Ahab, stands tall

with a strong, commanding presence — but the similarities end there.

Captain Cale — whose name may be derived from the Latin term “portus cale” meaning “warm harbor” — smiles easily as he

quietly explains the intricacies of tracking marine mammals off Honolulu’s

Waikiki Beach. Manning the wheel of the 90-ton, twin-hulled Navitek, as he has for five years, the captain scans the horizon for

the tell-tale wisps of spray forcibly expelled when a whale exhales and briefly

exposes his back to the sky and to the captain’s watchful eyes.

“Thar she blows,” the passengers call out eagerly, as if reliving the

romance of a bygone era. And then, showing her tail to the world, the whale is

gone from sight just as quick.

At this point, the captain makes a written notation of the marine mammal’s

relative position and so begins a playful, two-hour game of hide-and-seek. Cale

will turn the cruiser on a heading he believes runs parallel to the course of

the whales that usually travel in small groups, or pods, of two to more than a

dozen. After a few seemingly long minutes, if his mental calculations are

correct, the pod will surface again, only this time he will be in much closer

and moving along the same line and speed as the quarry.

On deck, Navitek’s naturalist Nona Hanapi shares her aloha spirit and

knowledge of the humpback whale with passengers from around the world. Not more

than 30 minutes after casting off, the first whale is spotted. Like a curious

animal, the Navitek draws in closer,

but stays a safe distance away — both in observance of the rules of the

Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary and for passenger

safety.

Hanapi, a native of Oahu who studied marine biology at Kapiolani Community

College in Honolulu, explained Humpback whales migrate from the Aleutian Islands

of Alaska down the western U.S. coast to the Farallon Islands off central

California and then all the way to the warm waters of the Hawaiian Islands.

Here, they mate and give birth every year beginning in November and ending in

May. At least 3,000 whales travel more than 3,500 miles in around five weeks to

find the warm, shallow waters off Hawaii. Visitors saw at least four different

whales this day, which is “about average,” Hanapi said.

Humpback whales also sing the loudest and most complex songs of all whales. They

have long, often recognizable sequences of sounds using the largest range of

auditory frequencies of all whales, often either too low or too high for humans

to hear. Only males sing, it’s believed, and then only for mating.

On board the vessel, whale watchers are also treated to a buffet luncheon,

comparable to any found in a Waikiki hotel, along with coastal sightseeing of

downtown Honolulu, Waikiki and Diamond Head, and sometimes Kahala and Hawaii

Kai, if that’s where the whales are that day. Everything in the

two-and-one-half hour tour is included in a reasonable single price with

substantial kama‘aina discounts.

If you want more intimacy in whale watching adventures, there is Deep Ecology,

based in Haleiwa. Known for its six-passenger, up-close-and-personal tours using

high-speed inflatable watercraft, Deep Ecology tours yields more thrills while

observing nature. Getting wet is part of the fun, according to tour operators.

“Our tours are a magical experience,” said Pat Johnson, owner of Deep

Ecology. “By limiting the number of passengers, we can offer a special tour

with a personal guide. The excursion talk seems more like colorful dinner

conversation than a conventional tour boat.”

To Hawaiians, whales are often viewed as a symbol of the Hawaiian god, Kanaloa

- the god of fish and ocean animals. Humpback whales — or na

kohola — are found worldwide, visitors learned. Although believed to have

arrived off Oahu long before mankind first showed up around 600 A.D., the first

written accounts of the humpback here didn’t appear until the 1840s.

Just 20 years ago, the humpback was an extremely endangered species. Then, in

1992, the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary was created

and formally approved by all levels of government in 1997. Since 1990, the

humpback whale population has grown from an estimated 1,000 worldwide to nearly

10,000 in the north Pacific Ocean alone –- and up to one-half of those visit

the sanctuary each year.

Every winter, the sanctuary conducts a land-based whale count, positioning

volunteer observers at various points on most of the state’s islands,

including Oahu. On the last Saturdays of January, February and March, volunteers

spot and count the whales, many of which can be individually identified by the

distinctive markings on their tail flukes.

In addition to the annual count, the sanctuary hosts periodic, informal

land-based whale watches at various Oahu locations including Diamond Head Scenic

Lookout, Lana Lookout, Halona Blowhole and Makapuu Point.

If staying high and dry is your thing, or if you’d really like to know more

about Megaptera novaeangliae and

whaling, visit the Bishop Museum’s Hawaii Maritime Center, located on Pier

Seven at Honolulu Harbor near the Aloha Tower Marketplace. The complete skeleton

of a humpback whale that washed ashore on Oahu is displayed in the permanent

whaling exhibit.

Docked in the water at Pier Seven is a 19th century four-masted sailing ship of

some historical significance. No, she’s not the Pequod,

a fictional three-masted Nantucket whaler, old and worn even before the great

white whale rammed and sank her.

Here sits the The Falls Of Clyde, the

world’s last remaining fully rigged, four-masted schooner. Although built in

1878, a few years after the whaling boom had past, it is still reminiscent of

those days when the cry, “thar she blows” could be heard coming down from

high atop the main mast and echoed below by all hands on deck.

Aye, Captain, thar be whales here, and

there will be for a long time to come. Watch and see.

Contact

information for companies and agencies mentioned:

•

For Atlantis Adventures’ Navitek whale watching tours, call 973-1311.

•

For Deep Ecology’s open boat tours, call 637-7946.

• For the national sanctuary whale count, times and dates of land-based whale watches, or to become a volunteer on Oahu, call its offices at 397-2651, ext. 253.