|

.

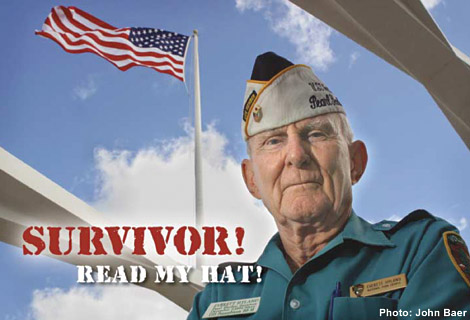

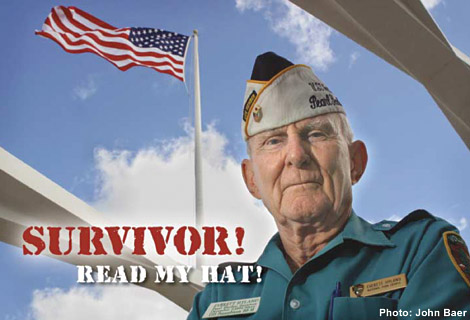

................Everett

Hyland, WWII veteran and Pearl Harbor survivor at the USS Arizona Memorial.

By:

Kathryn Drury

Oahu Island News

I’m sure many people ask Everett Hyland what the morning of

December 7, 1941, was like – but I’m not about to. Gee, Mr. Hyland, tell

me about how you were above deck on the USS Pennsylvania when the bombs fell

during the attack on Pearl Harbor. How it was early one Sunday morning when

the sky unzipped and hell slid onto your head. How the ships around you

started exploding and ripping open from their own ammunition igniting. Men

trapped underwater, and above, billowing smoke. You were so badly wounded

that you were almost given up for dead; you didn’t even know where you

were until Christmas. How you were only 18 years old. No, I’ll leave that

part alone. I’ll just ask you who you are.

For a guy who just celebrated his 80th birthday and has survived

cancer, not to mention horrific war wounds and numerous resulting surgeries,

Everett Hyland remains a man very much in the prime of his life. Trim, with

white hair, he looks younger than his years. He energetically greets his

coworkers at the USS Arizona Memorial, where he is a volunteer. He’s the

kind of guy who answers, “Fantastic!” when people inquire as to how he

is that day, the kind of guy who jokingly claims to volunteer at the

memorial solely for the purpose of checking out the young, shorts-clad

tourists. He is proud to be the only survivor who takes part in the yearly

water cleanups, done around the submerged battleship Arizona. “I don’t

do much, to be honest, but I put on my wetsuit and get in there!”

After a childhood growing up in the Northeast, Everett Hyland followed his

brother – who was two years older and had enlisted as a marine sergeant

– into the military. Before World War II, Everett explains, “Enlisted

men were considered ‘bums’, you couldn’t go into certain areas or

restaurants.” Still, Everett

enlisted in November of 1940 and went through radioman’s school in San

Diego, California. His brother – his only brother – was later killed at

the Battle of Iwo Jima.

A Radioman 3rd class, U.S. Navy Retired, Everett has volunteered

at the USS Arizona Memorial since 1995 and as a survivor, helps relate the

Pearl Harbor story to the 1.5 million visitors who pass through each year.

He says the National Park Service, which runs the memorial, is flexible

about what the volunteers choose to discuss, but as most people only want to

see the Arizona – one portion of the memorial but the best-known icon of

Pearl Harbor – he focuses on that. He seems puzzled by the visitors who

come, seemingly out of duty, but who neglect to read any of the signs about

history or the people involved. He especially hates it when visitors ask

him, “Were you here when they bombed Pearl Harbor?”

Not only is he wearing a color-coded teal shirt that helps clue them

in, he says, “It’s on my hat: Survivor! Read my hat!”

“The best way to describe

Everett is that he’s a representative of that WWII era,” says Brad

Baker, public affairs officer at the memorial. “So many people from that

time went through terrible ordeals, but they came back, put it behind them

and built America. And that’s how Everett is. He pushes away the idea

that he did something special; he doesn’t present himself as a hero. And

that’s important, because so many of the movies we see glorify it. He

shows the honest perspective. To him, he was just doing his job.”

When asked how becoming a

veteran affected the course of his life, Everett shrugs. “Veteran?

It’s just a word. There are 16 million WWII veterans, and now with the

military over in Iraq, as soon as they step out of uniform, they will be

veterans.”

On the morning of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Everett was aboard the USS

Pennsylvania; nicknamed the “Pennsy”. The

ship was in dry dock, undergoing maintenance. Everett’s duty as a seaman

included antenna repair, so he was above deck when the Japanese raid

started. He and the crew responded by bringing ammunition out onto the

deck to arm the 3-inch, 50-mm anti-aircraft guns. After two hours of

torpedoes and bombs, the attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet was over,

strewing behind it the Arizona, destroyed beyond repair; the Oklahoma,

which capsized; the West Virginia and California, resting on the bottom of

the harbor; a nation at war; over two thousand dead; nearly two hundred

demolished planes, and one Everett Hyland, of Stamford, Connecticut,

barely alive.

After nine months of rehabilitation, Everett returned to sea, serving

aboard the USS Memphis and also at the Naval Air Station in Charleston,

South Carolina. He was discharged from the Navy in November, 1945, after

earning seven campaign ribbons for involvement in the Asia-Pacific, the

Atlantic, and the European-African theaters, as well as a Purple Heart,

awarded to members of the armed forces who are wounded in combat. When

he left the military, he had no way of foreseeing that one day his

granddaughter, Annamaria, would stand before him at her 1996 graduation

from the U.S. Naval Academy. A lieutenant, she is currently stationed in

Asia, and Everett smiles most broadly when he is talking about her.

After teaching science and living in Nevada for many years, Everett met

his current wife, Miyoko. She was working for a Japanese travel agency and

he was in Hawaii for the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor.

“She’s a new model,” he jokes, as he was married previously. She is

now an employee at the memorial. The couple travels to Japan every year.

“I go for the hot springs and to see Miyoko’s family,” he explains.

“We go every October when the leaves are turning colors and the air is

cool and the springs are hot. It’s wonderful.”

As he describes the hot springs, he looks completely transported

and I can see Japan through his eyes: the steam from the hot-spring bath (onsen)

rising, the snow-topped mountains off in the distance, the glow of yellow

leaves fluttering downwards – it is a lovely vision. In Japan, baths are

about more than cleanliness; an important cultural element, the daily

ritual of a bath signifies purification, relaxation and family connection.

It is a centuries-old way of soaking the world’s troubles away and

emerging renewed in both spirit and body.

Everett is one of the many veterans and civilians who are able to harbor

no resentment after war, but certainly not everyone can let go. For

example, he met a retired military man recently at the USS Arizona

Memorial who looked around and asked him, “What are all these Japs doing

here?” “I told him,

“They are Japanese,” said Everett, “and I thought, ‘you’ve been

sick for this many years?’ It’s the business (of war); it’s not

personal.”

As part of his activities as a Pearl Harbor veteran, Everett places a

wreath at the Arizona Memorial during ceremonies held each year on

December 7th. He explains that Jiro Yoshida, a former Zero

Fighter pilot with the Imperial Japanese Navy, now joins him in placing

the wreath during the ceremony.

Like many of the Pearl Harbor survivors, he has participated in several

symposiums, such as one on the 60th anniversary of the attack

at Pearl Harbor held in 2001, which brought together American veterans and

Japanese Zero pilots.

Everett’s former adversary was a man named Otawa. “I had dinner with

the guy who put me in the hospital for nine months,” Everett says

matter-of-factly. At the dinner where the two men met, with his wife

Miyoko serving as the translator, they discussed the attack and came to

the conclusion that Otawa had most likely been the pilot who had bombed

the Pennsylvania. They will never be totally certain; it was hard for

pilots to know exactly where the bombs they had dropped landed. Those were

the days of gravity release, rather than the precision target-seekers of

today’s warfare. Obviously not harboring any ill will, Everett points at

his hat, which has a small pin on it of the American flag and the Japanese

flag, intertwined. “He was just a young guy doing his job.”

“Wars are crazy,” he says. “I’m not going to go with a sign or

anything, but I spent 28 years in a classroom and I used to tell the kids

that whether you are killing someone in a war or killing them on a street

corner, there are better ways to solve problems.” He tells the story of how one of his students, about to go on

a family trip to Europe, explained that he needed to see the places of his

heritage before there was another war. “I asked him if he thought there

was going to be a war, and he said, ‘Mr. Hyland, why would the next

2,000 years be any different from the previous 2,000?’”

Today, Everett Hyland lives in an Aiea Heights house that overlooks Pearl

Harbor. But when asked about the symbolism of this, he sees not a place

where he nearly died, but merely a nice view, a stretch of water. He seems

more excited about the ofuro – a large Japanese tub – built into his

house.

The USS Arizona

Memorial visitor center is open 7:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., seven days a week.

Run by the National Park Service, tours start every 15 minutes and are

free; tickets are distributed on a first-come, first-served basis. For

more information, call (808) 422-0561. A Memorial Day Ceremony, held from

7:45 a.m. to 9:00 a.m., is open to the public.

|