|

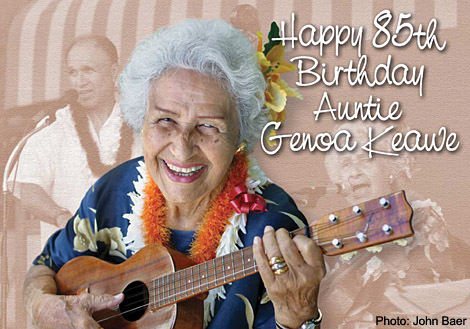

A Legendary Hawaiian Performer By:Kathryn

Drury Despite

her years, traditional Hawaiian vocalist Auntie Genoa Keawe still boasts a

voice as clear and sparkling as spring water. She’ll grab hold of an

impossibly high note and then, when you’re impressed by the mere fact

that she hit it, she’ll effortlessly hold onto it – lifting overhead a

crystal orb of pure song – for what seems like five minutes. Few artists

have laid claim to Hawaiian music as completely as Auntie Genoa has and

after 70 years in the business, she’s as respected and beloved as

royalty. On Oct. 31, this Halloween baby celebrates another milestone: her

85th birthday. When

I met Ms. Keawe for our lunch interview, she emerged from a car sporting

“GENOA” license plates. She’s gracious and small, with beautiful

caramel skin, fluffy gray hair and a touch of begonia-pink lipstick. Just

as she has wooed audiences for decades, she has obviously also charmed the

staff at the Waikiki Beach Marriott Resort, where, for the past 9 years,

she has performed weekly. They open doors for us, usher us in and stop by

to kiss her hello. Did

you listen to music as a young person? Was there a radio or record player

in your home? Did

anyone teach you how to sing? Did you have to study music? You’re

originally from the Kakaako area of Honolulu. I read that you were born in

a stable; is that true? In

your early music career, you supplemented your income by working as a taxi

driver. Were you the only woman doing

that? You

had 12 children. You must have started young. How old were you when you

married your husband, Edward? Can

you explain the concept of “chalangalang?” I’ve

read that you give thanks to John Almeida for giving you a start, because

he invited “anyone who can sing” to come onto his radio show on KULA,

and you went in and performed. Were you nervous singing live on the radio?

I

understand that your husband’s mother spoke Hawaiian as her first

language and taught you, so you are able to sing in both Hawaiian and

English. Has your language phrasing changed over the years? No. But if

I had been singing something one way and I’d find out it was wrong, then

I would correct it. Some of the younger artists have a hard time

pronouncing Hawaiian words. I

think you’re best known for your falsetto vocal styling. In American

falsetto, singers try to hide the point where their voice changes

register, to make a smooth transition. But Hawaiian falsetto reminds me of

shifting a manual transmission on a car. Singers stress the “break” in

the voice as it pops it into a higher register. Can you explain how you do

it? When

you perform, you smile the whole time; you’re like a ventriloquist! How

do you smile, and more importantly, how do you breathe, while singing? How

can you sustain a note for as long as you do? Some

singers find their voices change as they mature. Have you found this to be

true, and if so, what effect has it had? You’ve

been recording since 1946, first on the 49th State label and later on Hula

Records. In 1966, you started your own company, Genoa Keawe Records. Why? How

did “Alika” become your signature song? Do

you surf? You

have a huge repertoire, singing and playing your ukulele to traditional

songs in Hawaiian as well as hapa haole music. How has the Hawaiian music

scene changed over the years? You’ve

been honored with the National Heritage Fellowship, presented by the

National Endowment for the Arts – the highest honor the country can give

to a traditional artist. And you’ve won many Na Hoku Hanohano awards.

Two years ago, you were inducted into the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame.

What are your goals for the future? As we were leaving our lunch

meeting, a gentleman seated at a table near us flagged me over. “Who is

that?,” he asked, curious about the interview. “Was she a singer?”

“No,” I answered. “She is a singer.” You

can hear Genoa perform every Thursday evening from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. at the

Waikiki Beach Marriott Resort. Grab a mai tai, order some sashimi, and

enjoy the ocean view while listening to one of Hawaii’s living legends. Also, on October 24th

there will be a special birthday celebration for Genoa Keawe at the Hawaii

Theatre Center, 1130 Bethel Street. Tickets and more information can be

obtained by calling 528-0506. |